Current conversation in the United States focused on democratic decline represents broader discussion and observation of democracies across the globe. Democratic ranking indexes, such as Freedom House and the Economist Intelligence Unit, draw attention with reports such as “democracy in crisis” and “freedom of speech under attack.” Some of the most robust and seemingly solid democracies have begun to sway following the rise of populists, corruption, economic crises, media crackdowns, attrition, and other, perhaps seemingly innocuous, reforms.

India is one such state that is often praised for its large and “robust” democracy. The world’s largest democracy with over 1 billion people was established relatively quickly following independence from Great Britain. While the interim years were marked by horrific bloodshed and migration between India and the newly formed Pakistan, a constitution sought to address the most pressing issues: establishing fundamental civil rights, disabling the hierarchical caste system, creating equal opportunity and economic growth, decreasing economic inequality, addressing religious divides by creating a secular government, and carrying out free and fair elections. In 1950, the new constitution passed and created a secular parliamentary democracy with an independent judiciary.

While strides have been taken in certain areas, many of the same issues persist and are contributing to current democratic backsliding. Caste and Religious divides, political corruption, and, more recently threats to media freedom and civil society raise concerns of India’s democratic trajectory. Between 2016 and 2018 India fell in Freedom House’s index from “free” to “partly free,” the Economist Intelligence Unit dropped India’s ranking and rating to a “flawed democracy” between 2016 and 2017, and Reporters without Borders dropped India’s ranking 3 places regarding media freedom and censorship.

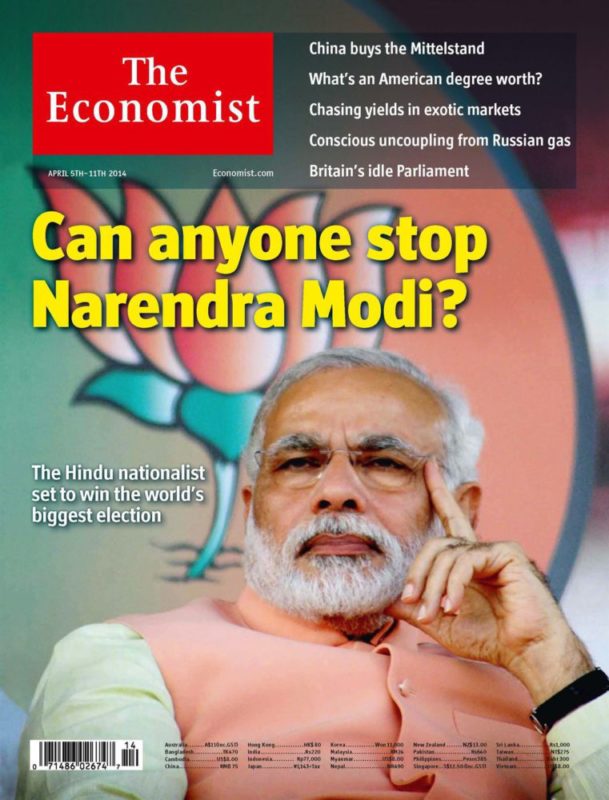

The source of decline is largely connected to religious identification, declining pluralism, and diminishing governmental secularism. Relationships between the Hindu majority and Muslim, among other, minorities have not improved and begun to degrade most noticeably since the 2002 Gujarat riots. The Hindu-Muslim riots resulted in over 1,100 deaths, the displacement of 150,000 people, the destruction of 20,000 Muslim homes and businesses, and 360 places of worship. India’s current Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, was the state’s chief minister at the time and was criticized for inciting violence and inadequate response. The events in Gujarat set a ton of religious bias around Modi, a perception only enhanced by being a politician of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

The BJP’s identity is in line with that of a religious and Hindutva ideology, which considers non-Hindus or those belonging to religions that do not see India as their holy land as full citizens. With the slow dissolution of the caste system and the development of communication technology, may citizens have begun to regard religion as a primary form of identity. The 2000s saw and a further rise in popularity of a right-wing neo-nationalist Hindu front.

The BJP was able to secure a majority in the 2014 election using Modi as the figurative image of the party. This was a step away from previous elections that had a party, rather than candidate, focus. Combined with the right-wing Hindu supporters and broader electorate, by setting aside religious messages in favor of economic growth, reforms, and development, Modi and the BJP came to power. While candidate focused campaigns are the norm in the United States, the technology, media, and candidate driven campaign that Modi engaged in was a definitive step away from Indian political party norms and edged on populist rhetoric.

The first years of Modi’s presidency were marked by efforts to resolve the issues that he campaigned on, with greater focus on a development and economic, rather than cultural or religious, agenda. However, since the election, and 2016 especially, secularism and religious equality have continued to decline.

Communal violence and anti-Muslim sentiment has continued to increase since the 2014 election. Though the number of deaths due to communal violence has fallen, the number of incidents has increased overall, with Muslims disproportionately likely to be injured or killed. The rise may in fact be due to right-wind Hindu nationalists, who have instigated many of the clashes, feel legitimized by Modi’s election.

The rise in violence against Muslims is not instigated directly by federal or state governments. However, as Modi and the BJP have continued into their term, their actions have slowly begun to shift back to the party’s religio-cultural platform. 2015 and 2017 saw the tightening of cow slaughter laws in the states of Maharashtra and Gujarat, and the subject played an important role in the most recent Bihar and Uttar Pradesh elections. These laws reflect increasing violence against Muslims relating to cow slaughter. Since Modi’s 2014 election, there have been at least 61 attacks, with 37 additional incidents occurring in 2017 alone.

2016 saw the appointment of Yogi Adityanath as Uttar Pradesh’s chief minister after the BJP won a three-fourths majority. The head priest of Gorakhnath Math, a politically active Hindu sect and a hardline Hindutva, Adityanath exemplifies the melding of Hindu-nationalist ideology and government.

As the BJP have continued to win state elections on an increasingly cultural agenda-centered platform, competing parties have begun to use similar tactics. The largest competitor, the Congress Party, has begun to ignore Muslim minorities during state campaigns, instead appealing to other communities and visiting Hindu temples as opposed to mosques. The approach is largely regarded as a strategy to not appear as Muslim sympathizers and is a step away from the Congress Party historical position as a “catch-all” party. The most significant result of these newer campaigning methods by other contenders is that pluralism may be at increasing risk as religious identity begins to define one’s legitimacy as a citizen.

The root cause of India’s current backsliding, as stated earlier on, is the continuation and exacerbation of systemic issues. A rising Hindu-nationalist movement shows a significant flaw in India’s democracy, namely that India was never truly a secular democracy as religion is allowed to play out directly in politics and party platforms, as with the BJP. This fact provides a significant opening for the erosion of secular, plural and political norms.

Addressing erosion requires Modi, the BJP, and other parties to make firm commitments to pluralism and secularism, ideally in the form of a constitutional amendment or the banning of official association between parties and religious bodies. Additionally, steps need to be taken to create outlets for the opposition to voice concerns and act as whistleblowers to call out infringements on democratic norms and rights. Violence against journalists is a rising concern, as they are increasingly the targets of violence, death threats, and smear campaigns. Given decreasing ratings in media freedom form 2016-2017, the outlook does not seem very optimistic.

The current trends point to a slow, yet further decline, in the health of India’s democracy, there are some notes of hope. India has addressed many of the large issues that the country faced at the start of its democracy and was able to form the world’s largest democracy despite them. India was not seen as having the “pre-conditions” for democracy in 1947, but was able to create one defined by robust institutions, an independent judiciary, and widespread political participation. India has repeatedly faced social, governmental, international, economic, and violent struggles, but has managed to pull through with its democracy intact; however, analyzing its current democratic state shows that it has yet to defy odds again.

Photo by The Economist Print & Digital, “Can Anyone Stop Narendra Modi?”, Creative Commons Zero license

Thank you, Anne, for your post. It seems like secularism perhaps is not possible for India as candidates’ campaigns are based on their religious backgrounds. The majority of candidates and political leaders are Hindu, however which has legitimized anti-Muslimism sentiments as there is little to no representation. I wonder how secular practices might be applied in India, when religion seems to be definitive of its culture and identity. As seen with European countries, such as France applying Laïcité, secularism has not been successful in promoting pluralism, but rather the opposite. Secularism has masked anti-Muslim policies and legitimized anti-Islamic sentiments. India is promoting the same anti-Muslim attitude while also allowing for the 1,100 deaths, the displacement of 150,000 people, the destruction of 20,000 Muslim homes and businesses, and 360 places of worship, as you noted in your post. The separation of religion from politics seems to ingrained, but adopting pluralist practices seems more reasonable. How much power does the government and the people want to lend itself towards religion, however, especially when it is such a contested area of concern and conflict. Candidates cannot rely on their representation of religion to secure positions in parliament. While there should be a breadth of representation. Candidates must be qualifying above all else in order for voters to not be reliant on voting based on religious affiliation. With most political leaders being Hindu and such leaders are working hard to push out opposition groups, there seems to be little hope. I don’t think religion should be denied a place in the political conversation because India is heavily based on the religious and cultural histories as a nation. There needs to be harsher implementations of checks and balances if religion is to remain a center piece of Indian politics.